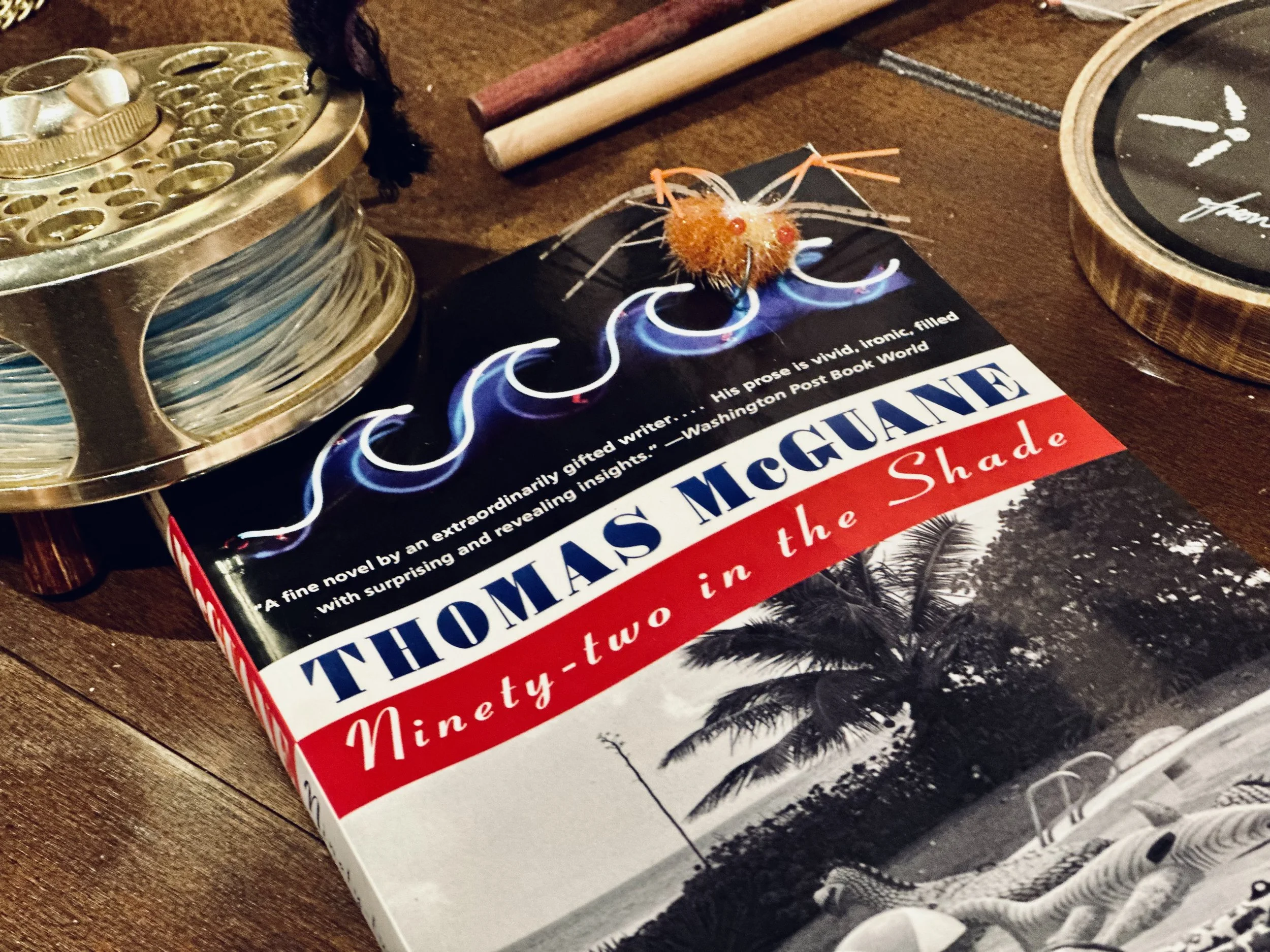

Review of 92 in the Shade by Thomas McGuane

Thomas McGuane’s 92 in the Shade (1973) is one of the most distinctive novels to come out of the Key West literary scene, a feverish blend of sunburnt absurdity, lyrical beauty, and existential wandering. On the surface, it’s the story of Thomas Skelton, a drifting, disenchanted young man who decides to become a flats–fishing guide in the Florida Keys—an ambition that entangles him with a rival guide and draws him into a violent, almost mythic conflict. But plot is rarely the point in McGuane’s early work. What matters is the mood, the manic comedy, and the raw sensory intensity of the world he conjures.

The novel reads like Key West itself: hot, unruly, seductive, and a little dangerous. McGuane captures both the romance and the rot of the islands—the guiding culture, the bars, the hustlers, the reefs and mangroves, the feeling that life is simultaneously drifting and accelerating. The book has the energy of a youthful writer pushing every boundary of voice and form, and because of that, it still feels startlingly modern.

McGuane vs. Hemingway: Two Florida Writers, Two Different Universes

Though both authors share an association with Key West, McGuane’s prose could not be further from Hemingway’s. Where Hemingway is sparse, declarative, and deceptively simple, McGuane is lush, abstract, and exuberantly verbose. Hemingway pares sentences down to the bone; McGuane pours on language until it almost vibrates.

Hemingway gives you a clean horizon line: short sentences, physical action, moral pressure created through omission.

McGuane gives you a psychic heatwave: tangled metaphor, surreal humor, and descriptions that thrum with color, sensation, and emotional distortion.

Reading McGuane can feel like stepping from the stillness of early morning water into a full noon blaze—his prose is humid, dense, and sometimes overwhelming. He writes as though intoxicated by the sensory world, insisting that every detail pulse with life, danger, and strangeness.

This difference is often what divides readers. Admirers of Hemingway’s minimalism sometimes find McGuane’s sentences too “busy,” too saturated with imagery, too deliberately abstract. But in 92 in the Shade, that style is precisely what gives the novel its identity. It’s not supposed to be clean; it’s supposed to feel like the delirium of heat, salt, ambition, and youthful recklessness.

Verdict

92 in the Shade is a novel that could only have been written in the Key West of the early 1970s, when McGuane and his circle—Harrison, Brautigan, Buffett, de la Valdene—were forging a new kind of American coastal mythology. It is funny, sad, violent, surreal, and unforgettable. It’s not an easy book, but its difficulty is part of its reward. McGuane captures something essential about youthful ambition, the seduction of the sporting life, and the manic brightness of the Florida Keys.

For readers willing to immerse themselves in its heat and hallucination, 92 in the Shade remains one of the most original American novels of its generation—and arguably McGuane’s most iconic work.